Ancient Melodies

Discovering a forgotten Chinese novel and a sino-british literary relationship between Virginia Woolf and Ling Shuhua

The Shijia Hutong Museum @ No. 24 Shijia Hutong

"I (Ling Shuhua) am determined to be a writer in the future...So I dare to ask you to take me as your student. There are so few female writers in China, so the world does not know anything about Chinese women's thoughts and lives. This is very unfair considering their contribution to humanity."

- Recollection of a Few Letters

Ling Shuhua

On one of my first visits to Beijing I was booked to stay at a hotel on Shijia Hutong in the Chayangmen Residential District, a few kilometers east of the Forbidden City. I’ll admit I didn't really know what a hutong was at the time - the hotel was simply near where I needed to be for work, looked comfortable from the photos, and wasn't too expensive. But as I stepped out of my taxi into that dark narrow alleyway, I could feel my explorations of the Beijing hutongs were just about to begin.

First morning in Shijia Hutong and jet lagged, unable to sleep, I found myself up before dawn, walking the length the alleyway before the hotel breakfast opened. In pale light the red lanterns outside swayed in the breeze. A few street sweepers were out besides their carts. A trickle of elderly walkers were trailed by little dogs. Bikes and mopeds were being wheeled out from the tangled courtyard residences of the hutong. Beijing itself was unfolding, coming alive as if some giant mechanical toy set off by the rising sun held over the east end of the narrow alley.

At breakfast, I was to learn from a leaflet at my table that the Shijia Hutong Museum, in part funded by a charity the then Prince Charles headed up, was less than 100m away from where I was sitting - the first such museum in Beijing to attempt the preservation of hutong memories.

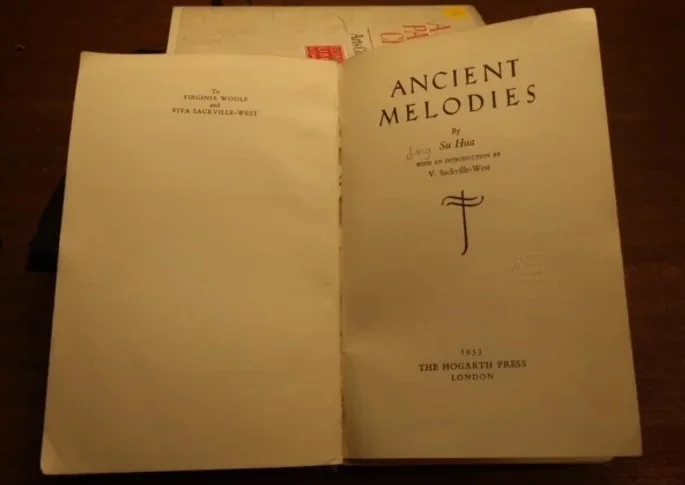

Ancient Melodies

Ling S(h)uhua (1953) Hogarth Press

Shijia Hutong Museum tells the story of a residence, a street, a way of life, and I feel in some respect, reveals something about the sleeping soul of old Beijing.

As you enter the museum, you are taken back to the start of the Hutongs and learn how these strict patterns of urban planning go far back into the history of Chinese cities and can be traced to the Western Zhou period (1046-771 BC). Comparisons are drawn with Manhattan and the grid layout of 19th century New York City. There is great continuity to the Hutongs that remain in Beijing and they give us a glimpse into the warren of a city that once would have been - centered of course on the heavenly astrological and architectural calculations of the Forbidden City. It is believed that Shihia Hutong dates back to the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) and is named after the Shi family ("Shijia" meaning "Shi Family"). The laws of the Ming Dynasty prohibited building illegal houses within the hutongs and were strictly implemented, meaning that even today we can still get a good sense of the architectural layouts from this period.

However, beyond the vast history of the Hutongs, it is the story of Number 24. Shijia Hutong as the home of the Chinese painter and novelist Ling Shuhua that forms one the central exhibition of the museum.

A model of the old Beijing hutongs - the warren now only extant in relative pockets of the city

Ling Shuhua (1900-1990) was the daughter of a provincial governor and sometime Mayor of Beijing during the late Qing Dynasty and describes her life growing up at no 24. Shijia Hutong in her autobiographical novel, 'Ancient Melodies':

"My bedroom had recently been arranged like a real studio. All the furniture had been selected by Father. there windows on two sides. One was facing a large purple wisteria, now in full bloom. The sweet smell was blown into one's nostrils until one almost felt one had eaten the flowers."

Upon marriage to Peking University professor Chen Yuan, the novelist inherited No 24. Shijia Hutong as her home and as stated in the exhibition, 'Ancient Melodies' was written in part to provide a foundation of reality against which to test the pervasive idea of the 'mysterious Orient' in the minds of western readers. Shuhua wrote mostly about daily life, regular experience - description, characters, detail. As I toured the exhibition outlining her works I was slightly bewildered to see the face of Virginia Woolf gazing out at me and a letter from her to Shuhua from the late 1930's, encouraging her literary endeavors:

"...so please consider writing about your life, and if you only write a few pages at a time, I could read them and we could discuss it. I wish we I could do more, and I send you my best sympathy for those of you who are experiencing the war...In fact, I would advise you to come as close to the Chinese both in style and meaning as you can. Give as many natural details of the life, of the house, of the furniture as you like."

How could this be the case? Surely there was an interesting story here? Indeed it was so (though not covered in the museum exhibition). In 1937 Ling Shua conducted an affair with the poet Julian Bell - nephew of writer Virginia Woolf, whom she met while the two were studying at Wuhan University. It was this relationship which opened the door to the long correspondence with Woolf. I've now learned of a novel covering the events of this literary love affair, written in 1999 by Hong Yin - 'K: The Art of Love', an allegedly gross misrepresentation and thinly veiled piece of sensationalism which has been vigorously rejected by Ling Shuhua's family.

One of the little dawn Hutong dogs

Ling Shuhua was to leave China for Britain in 1947 during the civil war. No 24. Shijia Hutong became a factory and, later, a kindergarten (1958-2002), before the creation of the museum. However, the story did not end there. The more I looked into the life of Ling Shuhua, the more fascinating I found the links pointing back to London.

With help from Woolf ’s friend and, of course, former lover, Vita Sackville-West (1892–1962), Ling’s memoirs were edited and published by the Hogarth Press (1953), the printing house of the Bloomsbury Group, with an introduction by Sackville-West.

Arriving home from Beijing and back in England I desperately wanted to get my hands on a copy of 'Ancient Melodies' and cannot quite convey the satisfaction and magic I felt at being handed a near pristine original Hogarth Press copy at the London Library; a copy which appears to have only been checked out a dozen times in the past 40 years.

Indeed, through internet searches I could only find a few articles on Ling Shuhua and her writings and so in the bowels of the London Library stacks I began my own reading of the Ancient Melodies.

As Sackville West observes in her introduction to the book, this "curious correspondence" with Ling Shuhua satisfied the romantic character traits of Woolf, envious as she put it of the "large wild place with a very old civilization." We learn from Sackville West how seriously Woolf took her mentorship role, sending 'The Life of Charlotte Brontë" to China amongst other books:

"It is easy to get books cheaply in London. Please never think of paying for them"

A typical hutong home from the 1950's or 1960's

Sadly we also learn that, "Virginia Woolf and Su Hua never met, for it was not until 1947 that Su Hua arrived in London with a pile of typescript in her luggage." But there can be no doubt about the impact of Ling Shuhua and Virginia Woolf's relationship, even if this was only ever on papers transported halfway across the world.

Reading Ancient Melodies and the subtle, powerful female characters recorded within, I could well imagine Ling reading Woolf's famous feminist treatise, A Room of One's Own (1929), inspired to keep writing, to gain her voice.

As Sackville West writes of Ancient Melodies, "some of the most entertaining passages in these memories are those which relate the complicated daily existence in the sprawling Peking household."

Ling Shuhua - returned to her old home on Shijia Hutong in her final days (1989)

Ling was a female Chinese writer who maintained a clear focus on expressing her perspective as being such. Her letter to Zhou Zuoren at the start of this essay demonstrates this point and Ling was part of legitimating women’s writing in China in the 1920's. It is perhaps ironic, and indicative of the long struggles of female emancipation, that Ling was to remain mute on her mentor Zhou Zuoren in later life. Some have speculated this was because his version of promoting women’s literature centred on a very male-oriented nationalist politics: e.g. women being allowed a voice if it served the right, male dominated, ends.

It's not my purpose here to review Ancient Melodies. However, to highlight how important such writings can be for our understanding of the past there are one or two quiet scenes worth covering. In a chapter titled “Great Uncle,” Ling's uncle, an educated fair minded man who becomes her good friends asks her:

"...what I would like to do when she grew up. I told him I should like to disguise myself as a man to take the Court examination. "My dear child," he said, "I am sure when you are grown up, examinations of all kinds will be open to women."

Through her writing Ling displays the dearth of opportunities for women in China when she was growing up. Elsewhere we hear of a China beginning to change. "Those new fashioned people certainly have missed something as they adopt the Western way," we hear Ling's father say, "They don't respect character writing. You see, character writing is the best way to make one's heart at peace."

I must say I raced through Ancient Melodies, almost like an excited child who opens all their toys at Christmas without truly appreciating what they are being given. I'm now looking forwards to a relaxed reading and taking in all of the delicate drawing's of Beijing which Ling included within the book - illustrations from her own pen.

Of course, much of traditional hutong life has now disappeared. As much as 90% of the original Beijing hutongs have gone, replaced by modern residential tower blocks and wide highways that run through the centre of the city. This said, the Global Heritage Fund estimates that about 600,000 of Beijing’s more than 20 million residents still live in Hutongs today.

Pockets of Hutong life are still present in Beijing. South of Tiananmen Square I got lost amidst the 'Citizens of The Emperor' and 'The long, thin alleys bordered by low, grey houses surrounding noisy, crammed courtyards' as described in Xiaolu Guo's 20 Fragments of a Ravenous Youth (2008). I was pleased to see at the Shijia Hutong Museum that within the Beijing City Master Plan (2004-2020) the concept of protecting Hutong-Siheyuan Architectural styles was included.

At the end of 1989 Ling Shuhua returned to China and to Beijing with the help of her family. She didn't have much time left. Before she died, her daughter and grandson took her on a stretcher back to Shijia Hutong. The children of the kindgergarten (which her former home was now used for) welcomed the novelist with flowers and singing. Taking in the scene the famous novelist was able to whisper, "mom is waiting for me to come home for dinner."

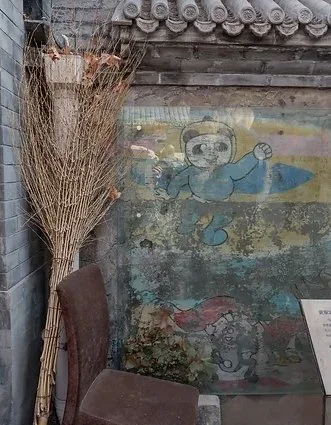

A wall painting from Shijia Kindergarten (1958 - 2002) - memory preserved

In the corner of the museum, a mural from the Kintergarten days is preserved - a fitting memory on which to finish my recollections of Shijia Hutong and the importance of history in the details. For beneath every history, another history.

And a bookshop is born…

A youthful journey to an old industrial village, climate conferences, anxiety, and the birth of a bookshop…

When I was seventeen I caught the train from Derby to the little village of Cromford. Here the world’s first water-powered cotton spinning mill was developed by the waistcoat popping girth of Sir Richard Arkwright. As a result, you could argue Cromford played a pivotal role in the development of modern industrial civilisation. Those who’ve visited the gloriously eccentric and creaky timbers of Scarthin Books can confirm that Cromford maintains its central position in the human story, this undoubtedly being the location of the world’s greatest bookshop. For me, it will never be surpassed. Whenever visiting family in Derbyshire I must return to Scarthin Books. A seasonal pilgrimage. The reason why is that trip when I was seventeen.

I can’t remember why I decided to visit. I was into The Smiths. I was a bit of a loner. I probably liked the idea of paying my £2 or whatever it was and traipsing off for the day to an old village on a little two car train. Shy, I nervously approached the desk to ask a question. The proprietor was almost scowling before I even began…

Scarthin Books, Cromford, Derbyshire - possibly the greatest on earth

“Sorry, I’m looking for a biography of Disraeli,” I said.

Now his expression changed. His entire disposition softened. Suddenly I was whisked into an ecstatic whirling discourse on the merits of various biographies of this 19th century Prime Minister. “This one is the best,” he announced, lifting a thick green volume from a box, on a shelf, somewhere in one of the many stacked rooms in this rabbit warren of shop, overlooking a mill pond, at the foot of the Peak District. I can’t remember who wrote the book. What I do remember is feeling like I needed to repay the enthusiasm of the bookshop owner by actually reading it. So I pulled out some details from the text and integrated them into an essay I was writing on “The Rivers Pollution Prevention Act 1876” (as relevant today as 147 years ago…).

Eventually the marks came back from the teacher and something remarkable happened. My history teacher, Mr. Oswald, was overjoyed. My initiative and further reading was commended. He pulled me into his office for a word. Not a bad word. A good word. You’ve got potential. Now I know this might sound strange to some but having been more interested in football results and whether I could learn a switch kickflip on my skateboard, the thought had never really occurred to me before that I could have academic potential. Life until then had been mechanical. I attended school, I had a Saturday job, I played sports with my mates. Something clicked. I could learn stuff. There was a whole world of things to know and knowing things could change your thoughts. And if you changed your thoughts, you could change your life and the world around it. That was the power of a bookseller.

Fast forward some 20 years or so and I’m on the floor, curled in the foetal position, gasping for each breath in tears. My partner Agathe comes to check on me, bring me tea every now and then. I’m telling myself to take it minute by minute and for some reason I focus on playing a golf game on my phone. I’ve given up on the art therapy of watercolour painting, now I’m clinging on. My body has gone completely and utterly haywire. My left upper chest feels as hard as a rock and is throbbing. My left arm has been tingling for months. My feet too. Even the left side of my face is going numb from time to time. What set off this monstrous reaction? We’d gone for breakfast at the local cafe. A lovely little cafe too. As we waited for our food to arrive on an autumn morning I could feel a wave coming again, a mad, non-sensical utterly overwhelming wave of anxiety that is hard to understand if you’ve never been through similar - and I really hope you won’t. My body was stuck, completely stuck in evolutionary flight mode. I had anxiety so bad even going to the local corner shop was an ordeal.

The escalation of this anxiety had been rapid. Previously I’d felt like I could take on a lot and take it in my stride. Although naturally nervy and quiet I’d also had a bit of courage to get through it and a deep desire to see and do things. As Morrisey had wailed to my teenage self, “shyness is nice and shyness can stop you from doing all the things in life you'd like to.” I’d been working for C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group since 2016 and by some strange twist of fate had become our HQ China expert, regularly visiting China to engage cities in climate action policies and build up our office in Beijing. All of a sudden I could hardly catch a bus, never mind an international flight.

The schedule at C40 was relentless in terms of travel and the variety of events and information I was dealing with. I remember one time being in Qingdao on the eastern seaboard and looking up from a huge meeting table. Our little delegation on one side with me in the middle, various representatives from the city of Qingdao opposite arrayed before us. Above the heads of their delegation were three portraits. Marx, Mao and Lenin. It was a long way from Derby. The job was full on. None-stop. Then the pandemic came and everything had to stop.

Playing my role, at the “8th US-China Energy Efficiency Forum” - singing another Memorandum of Understanding…

Life often makes sense in hindsight doesn’t it. We take that messy business of living and spin convenient narratives for ourselves. Well, what makes sense to me now is that the stopping did something to my mind and body. It was as though I couldn’t slow down whilst I had no control and nowhere to go. I was running into myself. Slowly at first I could feel anxiety rising inside me. Obsessively I would read the news, first covid, then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and finally climate change. The topic i’d been motivated to work on since I was a teenager - which I’d studied at university. I was reading everything I could on climate change after seeing the aftermath of wildfires on the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage across northern Spain. I couldn’t stop. New technologies. The latest research on the physical science. Diplomatic assessments. My mind lamented what could have been. What should have been. It was as if I had another dialogue with myself happening constantly. “Shut up,” I’d think lying in bed before inevitably scrolling and searching for more news at 4am.

The evening after the cafe incident I told Agathe I couldn’t take it anymore and shakily found the strength to drive myself to the local hospital. It wasn’t even the right place to go but in that moment I needed to do something. Soon I was speaking to a doctor and began to get some help. Slowly at first but then almost as rapidly as I’d descended into the pits of anxiety, life became manageable once more. Even writing these words I wouldn’t say I was fully recovered. Do we ever fully heal from such things? It will always be there. Lurking about…the sly little gremlin…but I feel much much better. And there is a reason I’m writing this.

The shop we went to see after returning from France in June

When I was at my lowest I read online blogs from people suffering anxiety. One man wrote a piece that I hung onto. He said that although the person reading his message won’t believe it now, it’s possible that you might look back on these moments as important and even ones you wouldn’t take away from your story if you could. He wrote about how his anxiety had caused him to reassess his life and changed his perspective dramatically, made him a better person. I wouldn’t say if given the choice that I wouldn’t take away the anxiety. Thinking about the worst moments almost brings back the sensation of soreness and pain in my chest. But I do understand how he could write those words. My own severe bout of anxiety caused me to realise how precious life is. And that I needed to be myself. My full self. In those climate conferences and meetings, I wasn’t always my entire self. It felt like I was acting a bit, playing a role, which though I was adept to do at times, never quite came as naturally to me as it seemed to for others.

I decided to start off 2023 by putting myself out there. That was my resolution for the year. No more stabilisers. Let’s just live and follow our passions. I decided to test the waters by recording a video showing people my favourite church, a question I’m often asked online and in person. To my astonishment that first video gained over a million views on instagram and even more on TikTok.

A few months later whilst visiting Agathe’s family in France we were lucky enough to visit the asylum where Van Gogh was a patient between May 1888 and May 1889. I’d always felt such a draw to his works, like millions around the world. Here I was where he’d conceived the Starry Night. I had to show people who weren’t as lucky as me to be here. These videos gained even more views. I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have made them without the anxiety. Strangely it helped. A bit of me stopped caring so much. Caring about what people would think or say or how they’d view me when recording these videos or writing these words. It’s what I wanted to do…so there go, do it. No big deal.

Preparing notes for a video on Van Gogh’s asylum, Saint-Remy de Provence, France

That’s when the recurring bookshop dreams came flooding back. In France. In the olive groves where Van Gogh wandered. Why didn’t we just do it? Me and Agathe had talked about it. On other holidays. In Cornwall. When on pilgrimages through England. Never before had I really had the feeling that we might do it. The let’s just dive in spirit…now it was abundant.

As fate would have it on the day we returned to England a shop was advertised in our home town, Frome in Somerset. At the bottom of Catherine Hill. A beautiful cobbled street that is doing its absolute best to survive in the world of online shopping and the factories of fragmentation that dominate our lives. This is a place of real community and the shop seemed perfect. It was small. Needed absolutely loads of work doing to it. We could see it though. See what it could be. So we decided to go for it. It really was as simple as that. Agathe would stay in her full time role but be a steadfast support throughout the process of setting up the business.

Long Live the Hedgerows. That had been my tagline on Instagram for a few years and it seemed perfect for the shop which we’d decided to call Sherlock & Pages. We created a few other taglines too. Riot for the Dormice (our logo is now a beautiful linocut of a hibernating dormouse). And No Magic on a Dead Planet. This was about inserting personality and reflecting our values. The idea of being your full self. Sherlock & Pages is a little bookshop which something unique and positive to offer an online audience as well as helping to maintain a tiny slice of this magnificent little country high street. In short we are a conservation bookshop. Conservation of all we’ve inherited and all we have a responsibility to pass on.

We’ve been documenting our journey on YouTube, very much in the let’s just do it mindset. If you can subscribe, like and comment on the videos (as long as you actually enjoy them) then that would really help. Elsewhere you can follow us on instagram, and the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, and of course browse our online shop which will be regularly updated.

I’ve got to say I’m slightly terrified about the finances. Bookshops aren’t exactly a goldmine, not least independent shops. We’ll have to fight for survival on the basis of our soul, passion and expertise. We already maintain a unique list of thought provoking and beautiful reads online. Our categories are a bit different. They reflect our values and interests. Our strength is nature writing though we cover much more - from heritage, conservation, landscape, craft, to our love of British landscapes, art, and history. All the major categories of larger retailers are stocked but done our way. Any support you could give us would be greatly appreciated. We are currently shipping within the UK and to the US and Canada. I hope we can add more countries soon.

Pretty soon we’ll be opening the physical shop. Hopefully by early November. After writing this I’m heading off to start off some of the internal painting. It’s none stop again. Yet I feel the spirit of living has returned - as the English band James once wrote, “getting away with it all messed up.”

P.s. If you or anyone you know is suffering from anxiety, don’t feel shy of seeking professional help. So many people have reached out to me and told me they’ve felt the same. Sometimes when so much awful news is in the world we can feel embarassed at turning inward and looking after ourselves. That’s what we’ve got to do if we’re going to be any use to anyone though.

Long Live the Hedgerows,

Luke

. guardian of the hallowed words

A Passion for Doors…

The greatest thresholds from my historic explorations…so far

A writhing phantasmagoria of a Norman church doorway at Kilpeck, Herefordshire

Doorways. Portals of ideas. Thresholds to new possibilities. What has become of the great art of the door? Show me a person with a wonderful door and i’ll show you someone with soul (or a big bank account…). Whilst today builders so often see these as a utilitarian feature to open and shut, the gothic church architects of the medieval world saw the opportunity to create the most mesmerising and symbolic of creations. In my travels to thousands of churches across England, i’ve always savoured a fine old doorway.

Here in this post I’ve collected my top 12 English church doors, which I’ve also included in my new calendar: “English Church Doors.” available to purchase from the shop.

It’s true, I haven’t included many northern doors in my list as yet. I wonder if an upcoming tour of the northern counties will change this? I say this as a thoroughbred northerner, raised in Derbyshire to families from Lancashire and County Durham…despite me being drawn to dwell amidst the gentility of the South West…

Anyway, let’s not get sidetracked, onwards to the great portals of England. In no particular order:

1. The Church of St Peter & St Paul, Salle, Norfolk. Angels swing censers to guard a 15th century rural church of epic proportions, seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

2. The Church of St Mary & St David, Kilpeck, Herefordshire. A riot of Norman carving. Dragons, grotesques, angels, a phoenix, beakheads, a basilisk, a lion. A writhing phantasmagoria of the 12th century imagination.

3. The Church of St Dunstan-in-the-East, City of London. An oasis in the city. Patched up following the Great Fire of London, bombed in the blitz, reborn as a public garden.

4. The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Berkeley, Gloucestershire. Built in the mid-15th century, an elaborate ogee crocketed arch marks the threshold of the Berkeley family chapel. Here the family arms are held by a pair of proud, watchful angels. Perpendicular gothic perfection.

5. The Watts Cemetery Chapel, Surrey. Designed by Mary Watts, over 70 villagers were involved in the creation of this stunning chapel between 1895 and 1904.

6. The Church of St Mary the Virgin, Isle Abbotts, Somerset. Early 16 th century high gothic drama. How we can imagine this scene when Saints would have once filled the niches.

7. The Temple Church, City of London. Sometime headquarters of the Knights Templar in England, this church was built in the mid-12 th century. A round church it reflects the design of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

8. The Church of St Mary, Patrixbourne, Kent. One of the quiet masterpieces of English Romanesque architecture. This little south doorway is tucked away a few miles walk from the great pilgrimage city of Canterbury.

9. The Church of All Saints, Lullington, Somerset. Sugar twist piers, chevron moulding, beakheads, Christ in Majesty and tympanum with dragons devouring the tree of life. The English imagination circa 1150.

10. The Church of St Edward, Stow-on-the-Wold, Gloucestershire. Visitors come from far and wide to see the famous yew lined door of this church, said to have inspired J.R.R Tolkein’s “Doors of Durin” as featured in The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

11. St Germans Priory Church, St Germans, Cornwall. Seven orders of Norman decoration on the great west doorway.

12. The Church of St John the Baptist, Barnack, Cambridgeshire. This Saxon doorway shouts out its great age. It is simple. It is crude. It has endured a thousand winters.

The Home of our Delight

The story of a nation, of revolutions and wars, emanating from the quiet Somerset village of Mells

The sky ominous, full of mischief. Passing through Great Elm we dashed from tree to tree, caught by a Gore-Tex clattering downpour, before sheltering on a small stone bench in the porch of the little village church. It wasn’t long before the sky turned, the rain calmed and a faint drizzle was drifting through the summer air.

Half an hour later we emerged blinking from the woodland valley through which we’d traced the Mells River. From a watercolour grey sky to full vibrant blue, onwards we went out into the open fields behind Mells. Ahead, the soaring perpendicular gothic tower of St Andrew’s. Two upper tiers of triple windows and buttress pinnacles leading up to yet more pinnacles again, a dazzling 15th century creation that proudly declares its elegance over the surrounding Somerset countryside.

There’s something about Mells. Once before I’d visited to explore the medieval “new street”, have a quick pint at the Talbot Inn, and rootle about the church. It’s a village that whispers to you: a quiet place with colossal stories to tell. You somehow sense it before you know it. Ushered from the meadows into the churchyard by a guard of yew trees, you are transported into ancient Mells, old England. You begin to hear the carefree laughter that would have once filled the sweeping lawns of the neighbouring Manor House. You imagine the frenzy of activity as the church was rebuilt all those centuries ago. A bittersweet nostalgia hangs heavy. You are aware of memories and emotions absorbed here for generations. It’s a place of deep resonance.

St Andrew’s dominating the sweeping lawns of Mells Manor

Mells would be just one of the many famed Somerset church towers we’d pass by on a week of pilgrimage. Built between the Black Death and the Reformation they collectively represent one of the nations most important architectural inheritances, said by the exacting chronicler of Somerset life, Peter Poyntz Wright, to ‘stand apart by reason of their style, their intricate decoration, and their great height.’ They cast their emblematic shadows over a certain idea of England; the crowning glories of that timeless combination: manor, church and village. The Albion of the imagination.

I admit, this trip was a counter offensive of sorts. My partner, Agathe, is French. As such, I needed to rally a response. A response to previous summers spent lazing in the unfathomably beautiful Provençal countryside, pastis in hand on warm summer evenings, lavender wafting over the village boulodrome before hearty dinners consumed at considerable length, on tables where ancient blocks of limestone radiate the days accumulated heat into lamp lit streets of near obscene charm. Yes. We needed a reminder of what dear old blighty could do. To search out the magic beneath our noses. To once again know that our home, the green and pleasant land, could deliver.

Every country lane, rustic pub, canal towpath, ruined castle, tithe barn, cottage, market square, field, hedgerow, stream, cathedral and church were to be ranged for the task. For this vital mission the “The Glastonbury Water Way” was settled upon. This hike was to be a break from the world. An escape from the pandemic. And in an age when the infinite troubles and trivialities of the world are beamed second by second into your palm, there was to be none of it. A news ban was imposed. Instead, our attention would be one foot in front of the other, immersing ourselves in the landscapes of Somerset. We’d be going on pilgrimage, along a 55 mile route devised by the good people at the British Pilgrimage Trust (BPT), linking the ancient springs of Bath to the mineral outflows beneath Glastonbury Tor. Having downloaded the route from the BPT onto the Ordnance Survey smartphone app, our main challenge wouldn’t be navigation but rather to contend with the climatic vagaries of an English summer.

Yet the first day on pilgrimage was glorious, a dotting of cartoon perfect fluffy clouds and a big lemony sun burning ever warmer. Looking over a landscape is always an elemental experience; to pass into a landscape on foot and up to its highest vantage points is an infinitely more profound experience still. Bath Abbey was our chosen starting point. Soon we were racing over the Palladian splendour of Pulteney bridge, ascending the suburbs and marching onto the limestone plateau of Bathampton Down. The city of honeyed stone dozed behind us. Our spirits high we powered on through meadows and down into cooling woodland on our way to meet the Kennet and Avon Canal at Claverton.

Pulteney Bridge, Bath Spa - at the start of our Glastonbury Waterway Pilgrimage

A heron followed us for a mile or so on the towpath, or we followed it, as it glided just above the water before settling statuesque for a moment. By mid afternoon we crossed the Dundas Aqueduct across the Avon Valley, constructed of Bath stone in the opening years of the 19th century. Here the boats drift over the river and the Wessex Main line railway below, carried on three big arches, embellished by doric pilasters and fine balustrades. How outrageous this must have once been. The demands of industrial efficiency set against the topography of the land. You can’t help but admire the entrepreneurial chutzpah. There they must have been, the assembled barons of coal, timber, and manufacturing wealth, lamenting the delays caused by canal locks and toll roads before someone finally said: “we’ll go right across.”

Up steep narrow lanes we reached Freshford by late afternoon, a secluded settlement nestled within its valley, made prosperous by the cloth trade which the mills, weavers’ cottages and large classical homes stand testament to. We soaked in the iconic view of the village's brewery chimney from church hill and I spied a pub on google maps. Not just any pub. Hanging baskets, 16th century, garden overlooking the water meadows. Perfection. The Inn at Freshford was one of those tranquil country spots, on one of those hazy summer evenings, where England is for perhaps only a handful of days a year near unrivalled. Provence wasn’t the only game in town.

Rested and nourished we made our way from the Inn to our campsite, past the romantic ruins of Farleigh Hungerford Castle. A few ramshackle but grand old farm buildings stood at the entrance, where scrumpy cider was served from a hatch. Plodding out from a lovely Jacobean looking cottage came one of the residents, who presumably helped run the site. He wore a wide smile - an insouciant pantalooned cowboy, veteran of Glastonbury Festival and early mornings at Stonehenge. Perhaps he’d been a New Age traveller in the early 90’s. Off he went along the lane and we headed to set up camp, where a gaggle of ducks came to inspect our camping gear. Two bottles of the cider and a pair of chairs provided by a neighbouring camper - bliss as dusk settled over our tired legs.

The old lane past the romantic ruins of Farleigh Hungerford Castle

Showers and rainbows marked the next day as we plodded our way out to the trendy market town of ‘Frome’ - rhymes with broom - by early evening. There’s a quiet English radicalism in Frome, returned, perhaps, to its rural origins. On the cobbled streets of this once thriving centre of the cloth industry you feel a gentle but distinctive buzz, redolent of the non-conformist families who once stood as the industrial grandees of this old settlement on the eastern slopes of the Mendip Hills.

The 19th century saw riots in Frome, partially as a result of mechanisation and competition from the emerging textile factories of the industrial north; temporary booms in cloth output during the Napoloeonic wars gave way to decline and a partial recovery through the tenacity of local foundries, printworks and breweries. For me what Frome does best is to perform that rarest of tricks in small English towns, which is to maintain authentic continuity without sliding into twee chocolate box preservation or the insufferable monotony and staleness of hollowed out high street capitalism. It is alive. It retains some independence. It isn’t perfect but the past ripples into a sense of the future. The future feeds off the past.

Today, that radical English tradition is upheld by a town council entirely made up of independents; a model that has attempted to eschew the factionalism of party politics in favour of “flatpack democracy.” Yoga mornings in the former Methodist chapel and pub meetings for the local climate emergency action group. That’s the vibe.

Standing on a street corner looking a bit lost in the centre of town we were near immediately asked if we needed help by a kind looking chap, sheepdog by his side. “Ah yes, I know that campsite,” he said, before assuring us it wasn’t far and that if we were in search of a drink before we set off on our final section of the day he’d recommend The Three Swans. “It’s good. In a very Frome sort of way,” he suggested. “Which means good but in a strange way.” I was reminded of the countercultural slogans adopted in Austin and Portland in the United States. Perhaps next it would be “Keep Frome Weird.” In fact, I’d wager such stickers already exist.

After a pint of Butcombe original we followed the trail laid out by the sheepdog man, north over several big fields. Settled in at our campsite we huddled around a little campfire as the wind began to pick up. Mells tomorrow, I said. Shuffling into our sleeping bags as the rain began to pitter patter on the tent I recalled my previous visit. It had left a deep impression even if it was just a fleeting detour on that occasion. This time I was determined to take it all in and follow my intuition to uncover the story of Mells.

That story, it turns out, is perhaps no better told than by reference to the woman now synonymous with the village: Frances Graham.

Manor House & Church, the Talbot Inn nestled behind…the holy trinity of English life

Frances moved to Mells in 1883 in her late twenties. Though she was marrying into the local landowning family, the Horners, it wasn’t to the live under the gables of their picturesque Elizabethan and Jacobean Manor House besides the church; it was to the altogether more striking Mells Park, set within a deer park a mile outside the village, a great whopping pile of forty bedrooms. First built in 1724 and later expanded by Sir John Soame to command the view above the Mells river, the Park had been conceived as a more befitting residence to the old manor. This was Frances taking high position in a land of myth and legend, of almost feudal deference from the village tenants, a place where time had seemingly stood still, in deep country, sleepy and ancient Somerset.

To her friends back in London this must have seemed a somewhat odd, even disappointing decision. The cosmopolitan daughter of a wealthy Scottish Industrialist and Liberal Member of Parliament, Frances had been immersed in the tenets of Pre-Raphaelite artistic life since early childhood - as at ease in Florence, Venice or Madrid as she was in the galleries and studios of her native Kensington. Why retreat to the rolling hills and the type of domestic monotony she’d only recently derided? Her exuberant, daring and witty society confidant, Laura Tennant, witheringly described the constraints of such a life as a surrender to “jam-pottism”, where only village entertainments and the duties of motherhood lay ahead. Yet, beneath the surface a more complex reality existed.

Mells was a decisive move. This was Frances taking control, distancing herself from the men who through inspiration, imagination and a shared artistic optimism had so far directed the principal trajectories of her life, all too suffocatingly. First there was her father: a man who the biographer of Frances Graham, Andrew Gailey, describes as “hard to reconcile.” A hard-nosed, pious Glaswegian businessman, liberal parliamentarian and patron of “some of the most sensuous and erotically charged paintings of the Victorian era.” As a prolific collector William Graham was fundamentally moved by emotion, groping for beauty and hope, as happy to buy works by the Old Masters as he was patronising some of the most daring artists of the age - Rossetti, Ruskin, Morris, and his favourite, Edward Burne Jones. Frances and her father were to form a partnership as she took on many of his artistic dealings, led on correspondence and organised major loans. By the turn of the 1880’s she’d become a society figure in her own right, within the urbane almost bohemian artistic set of London.

Then there were the artists and chief amongst them, Burne-Jones. Often Frances would walk to the end of the long garden of his ivy-clad house in Fulham and into the studio where he’d disgorge, on canvases piled high, a separate realm of romanticism and the imagination - a world set against the industrial scars and imperialism of the age. “When I was about 18 or 19,” Francis would later write, “Edward Burne-Jones, who was about 40, and living a quiet life, became my friend and poured into my lucky lap all the treasures of one of the most wonderful minds that was ever created.” She was to become one of his favoured muses. Indeed, her image radiates from some of the defining works of the period; moody dreamlike undertakings, full of Arthurian romance that encapsulate an artistic revolt against an increasingly mechanised, rationalised society. At some point, the lines between friendship and romance seem to have been confused. Burne-Jones, full of idealism and beguiled by the idea of a creative love; Frances, denied the education of her male peers and thirsting for the knowledge and pursuit of beauty as articulated by one of the iconic artists of his generation.

Questions remain over the appropriateness of this relationship. Were they briefly lovers? Was this an intellectual but ultimately platonic dalliance? We cannot be sure. We can only know in hindsight what Frances made of her relations with Burne Jones. Clearly an affection survived, despite his bumbling, capricious emotions towards her. A mutual respect endured over a quarter of a century until his death in 1898. Yet for all the attention of some of the great artists of her age, in 1883 Frances was to marry John Francis Fortesque Horner, known as “Jack”, heir to family estates held through eleven unbroken generations since the Reformation.

Frances as artist - her embroidery work: ‘the Love that moves the sun and other stars’ (c.1880) an embroidery work that hangs in the church at Mells

Jack appears to have been everything Burne Jones wasn’t: young, a member of the gentry, no doubt with a fine mind but possessing little interest in the arts and concerning himself with more practical matters - the maintenance of gates and agricultural machinery, tenant relations and the genteel goings on of the county social circuit. What can we make of this? Perhaps he represented safe harbour amidst the maelstrom of artistic emotion in which Frances was raised. Of course, he was also relatively wealthy and through his ancient family lineage possessed entree into the high society world of politics, ideas, and frivolity. Frances would have been keenly aware of the circumstances required to flourish, to gain a degree of intellectual and material freedom within the constraints of her time, as a woman. Mells and Jack could have seemed a solid bet. Here was a loving, supportive and peaceable man and a place to call home which could make emotionally and physically her own.

Frances certainly did make Mells her own. Passing through the almost flamboyant high gothic 15th century porch of St Andrew’s you are met by a dazzling embroidered artwork on the left. Distinctly Pre-Raphaelite, we walked through shafts of cool light to find it shimmering in faded shades of rose, sage and bright sky blues; a depiction of Dante’s vision of Heaven, where a resplendent mother is surrounded by eight children: ‘L’Amor che muove il sole e l’altre stelle (c.1880) ‘the Love that moves the sun and other stars.’ It is a stunning piece, designed by Burne Jones and embroidered by Frances herself. In 1893 it was exhibited at the fourth Arts and Crafts exhibition at the New Gallery in London, alongside several of her works. Standing before this piece after we’d reached Mells, a few trapped flies and bees dancing between the shadows and the trellised sunlight, the ghosts of Pre-Raphaelite dreams swirled around us.

Under the tower nearby we next stumbled across another stunning piece, a memorial tablet 8 feet high bas-relief in gesso, multicoloured light filtering through stained glass and modulating softly across its surface. The central image is of a peacock, a giant decorative tail weeping towards the floor. This too was designed by Burne-Jones in the Byzantine tradition whereby the peacock represents immortality and incorruptibility. It is an appropriate and loving remembrance of Laura Tennant, Frances’s great friend who tragically died in childbirth in April 1886. Though Laura was buried at her childhood home in Traquair, in the Scottish borders, Frances commissioned Burne-Jones to ‘capture her spirit’ and place it within the timeless surroundings of Mells.

Laura’s death was devastating to Frances and to the social grouping around her, which coalesced to become known as ‘The Souls.’ A fashionable society coming together of the clever and quick witted, The Souls preferred philosophy, poetry and literature to baccarat and booze. The core of the group were the latest progeny of four landed families - the Wyndhams, Balfours, Charteris’, and Grenfells. Many of political and artistic figures were to pass through the weekend soirees of The Souls and at some point would have come down to Mells, to stand where we did before a poignant memorial to one of their brightest stars taken too soon.

The memorial tablet to Laura Tennant by Edward Burne-Jones

Numerous characters who were to have a profound impact on world events during the opening scenes of the 20th century would have gazed up at a star filled sky from the sweeping lawns of Mells Park. An 1890’s belle epoch of liberal British life descended on this quiet English village. Chief amongst these and a name that still resonates in the grand pantheon of British historical figures - Asquith.

Frances met the future Prime Minister H.H. Asquith in the early 1890’s, when he was a young lawyer and Liberal MP on the make. Immediately they were drawn to one another, active minds colliding, even sparring, over society dinner tables. Tragedy soon drew the intimacy closer. Helen, Asquith’s first wife, died of typhoid fever in September 1891. It’s clear Frances became an emotional support, a lucid attentive mind to console and female company to lean on. As the months passed and Asquith recovered from the shock of loss they began to exchange a fizzing, playful, flirtatious correspondence. Pouring himself into his work he was invited to hold one of the Great Offices of State as Home Secretary in August 1892. He was just 39. The artistic muse became a political muse, attending debates in the House of Commons, sharing in cabinet gossip via letter or on Asquith’s visits to Mells, even providing edits and suggestions for his speeches and articles. Was there a future for the pair? However fancifully, the question must have been toyed with in spite of the complication of her marriage - which was ultimately stable, loving, and enduring. There was always someone else between them though. Frances’ friend Margot Tennant, Laura’s sister. Asquith adored her.

His quiet but persistent pursuit of Margot had always been met coolly. Yet his enduring devotion would prove decisive. In May 1893 a society novel, Dodo: A Detail of the Day, was published - an overnight success. A thinly veiled parody of high society, the book had obviously placed at the centre of its plot the depiction of an ambitious, self obsessed Margot. It was a sensation amongst the powerful and influential, as well as a cause of much mirth. The embarrassment for Margot was colossal. Worse, her position in society circles came to be genuinely questioned. She was the victim of some quite open and brutal mocking. Asquith was to stand by her side.

Frances would regret the moment she chose to place the novel on Asquith’s bed on a visit of his to Mells - which soon found itself fluttering through the air as it made its way from the window to the lawn below. His steadfast loyalty throughout this incident helped change her view of him. A man of stature, he refused to listen to anyone, including Frances, who indelicately hinted at Margot’s liabilities. By the end of the year they were wed. Though Frances and Asquith stayed in touch, the relationship was forever more on altogether different, more firmly defined territory. And the myth of Frances’ epic matchmaking would go on to be spun in her biography some forty years later. Such is the way we massage our pasts and claim narrative from the murky experience of life.

For a time the cleverness of Asquith and the intimacy which they’d shared sated Francis’ intellectual thirst. A thirst that not only wanted to know things but to be amongst them, to be at the centre of the events. She was always attracted to great minds. In the 1890’s we can imagine Mells to be a sort of idyllic retreat, a rural hub for the coming age of liberal politicians either born to govern or those who’d risen from the middle classes to claim their place. Both Haldane (future Secretary of State for War and Lord High Chancellor who in decades to come would host a small private party for Einstein at Mells) and Grey (future Foreign Secretary leading into the Great War) also visited Mells regularly. Journalists came to network and gossip. Even a young Winston Churchill would stride the Mendip Hills leading out from Mells.

In the middle of it all were the children. A new generation raised on the arcadian dream of Pre-raphaelite art, old master paintings, intellectual jousting, agricultural traditions, wild flowers, ancient buildings and rolling fields. Under Frances’ curating hand Mells Park was over the years decluttered and transformed into her fantasy vision - a star around which the grand firmament of liberal England swirled and gathered for a time. It must have been a thrilling place to have called home, in an age of growing confidence and ambition amongst their parents' circle.

Despite Jack being appointed Commissioner of Woods and Forests - a public office with a handsome salary - the Horners finances were never quite on as sure footing as their social connections would suggest. By 1902 they’d been forced to rent out Mells Park and decamp to the ancestral pile: Mells Manor, first brought into the family under murky circumstance by Thomas Horner, sometime steward to Richard Whiting, the last Abbot of Glastonbury (brutally dragged through the streets of Glastonbury and then hung, drawn and quartered atop the Tor). Rumour and myth had it that the nursery rhyme Little Jack Horner recounted a wicked steward of Glastonbury who “put in his thumb and pulled out a plum,” - the plumb being Mells and the pie being the dissolution of the monasteries.

The tumult of the dissolution of the monasteries ameliorated by the passing of the centuries and by opening scenes of the 20th Mells Manor had once more come to be the charming, if not entirely practical, spiritual centre of the Horner clan. It's remarkable that the English countryside and the quaint villages and towns that sit within it have so often been witness to such brutality and violence. How Mells must have changed in the winter of 1539. Whilst raised in the grand park, the children were to return from school and university to the manor first built by Glastonbury Abbey, dancing and playing under the dripping romanticism of their warped and gabled home beside the church. First born was Cicely in 1883, followed by Katharine in 1885, Edward in 1888 and Mark in 1891.

This was the time when Frances’ friendship and patronage of the young architect Edward Lutyens, whose career she helped launch, was to take on the Tudor and Jacobean soul of the manor and distil the spirit of old England through the prism of the Arts & Crafts movement. This idea of England still dwells in Mells, Lutyens’ signature dashed about the village in little moments of elegance and style. He was to add the walled gardens and a loggia, as well as the iconic entrance way to the manor - framing the high gothic church tower beyond. The more intimate scale of the manor, its low ceilings, smaller rooms and the inevitable evenings spilling out onto lush grass and the wildflower meadow, had required a more relaxed approach. Haldane still came to puff his cigars and the Asquiths remained firm fixtures at Mells; a tonic of calm away from the pressing affairs of state. Frances continued her needlework. Cicely painted watercolours in the gardens. Katharine read the poems of Yeats. For a time, before the shattering years, this must have been heavenly:

“We were very much in the political world. My dream had come true - Asquith, Haldane and Grey had more and more power in the State. I used to think that if Asquith were Prime Minister, Grey Foreign Secretary, and Haldane Lord Chancellor, all would be well with the world, and so it was for a time, before the shattering years broke us.”

Frances Horner (née Graham), 1933

From a cloudless sky the storm was coming in.

Bucolic Mells - how sweet life could be…

Mark was a beautiful, charismatic boy and he died in 1908 at the age of sixteen. It was scarlet fever. The night he died Frances had left him promising to come back and read to him the next day. During the night he called for her, “Mother, Mother.” By the time she arrived at 5a.m he was gone. Grief and guilt wreathed her. Her own brother had died at the same age. With Jack also suffering from the fever, she had to attend the funeral without him, the village turning out in all their numbers to support the family. Mark’s tombstone still sits in the churchyard. On this return to Mells we squatted down to make out these sad words beneath the lichen:

“Mark George Horner who died on March the third nineteen hundred and eight aged sixteen & who in his short & happy life called everyman his friend.”

A country lad at heart, Mark was adored in the village and in turn he adored the village, Somerset and all its agricultural traditions, much as his father did. Lutyens was commissioned to design a pretty three cornered stone shelter in the village as a memorial to him.

Life at Mells was changing forever. Mark’s sisters were married. First, Katharine in 1907 to Raymond Asquith (son of H.H.) at St Margaret’s Westminster; the reception at 11 Downing Street, home of the groom's father, then Chancellor of the Exchequer before his elevation as prime minister less than a year later. Raymond was perhaps the paragon of late Victorian virtue - handsome, tall and an intellectual blaze, moving from a First in Greats to election as an All Souls Fellow at Oxford in 1901. Though he was in some ways shy of the expectations placed upon him, or at least too self aware to fully gnaw at them with too much satisfaction, this was a time when such men were seen as destined to go on to enter the cabinet and help run the empire. Cecily came next, in 1908, eschewing her mothers high expectations and merely marrying the famed horse-trainer and fifth son of the 2nd Earl of Durham, George Lambton. Eighteen years her senior and without much money, George was however in possession of a fine reputation, this being enough to assuage his mother in laws' most severe judgements on behalf of her first born.

Naturally Frances turned much of her affections towards her last remaining son, Edward - heir to a lineage stretching back over four hundred years and in his mother's eyes a model of Pre-raphaelite purity; like Raymond, one of the next generation of men who would continue the liberal mission of improving society. Tall, good looking and academically able without being brilliant, from Eton to Oxford, he certainly fit the bill. And yet drinking and gambling debts were to be transferred from a third class degree at Oxford to a society riot in London, along with his flamboyant dress and tongue, whilst ostensibly reading law. Hedonism ruled the day. With the Great War on the horizon and Europe soon to be convulsed by war, Edward was roaming the streets of the West End mired in debt.

In fact, the new generation had created their own successor The Souls, a more colourful and boisterous set known at The Coterie. One infamous evening in July 1914 encapsulates an era, when Edward and Constantin Beckendorff, son of the Russian ambassador, held a boat party on the Thames. In scenes reminiscent of a Coterie jolly to Venice the previous summer, when drunken young bodies were flung into a moon kissed Grand Canal, Denis Anson was encouraged by Diana Manners to swim to the Embankment at 3a.m. He drowned alongside one of the quartet of musicians who’d been hired for the evening who tried to save him. Beckendorff also went in after him and somehow survived. Though the full details of the event were covered up, the papers were full of the scandal in the days after the tragedy. It summed up the irresponsibility and triviality of the fashionable set. As one contemporary was to write of Edward in his university days, but which could be taken as a wider critique of his generation of privileged Souls offspring, he was said to have had “no ambition but to sip honey.”

Symbolically, the outbreak of war was announced on the same day as a grand party at Mells. We can imagine the excitable frivolous atmosphere full of political talk and without any idea what horror was to come. Raymond Asquith noted that there was a “hell of a crowd here this weekend.” Soon the party was over.

Mark Horners’ little gravestone beside those of his parents

The sun broke over the fields of the Somme on September 6th after ten days of rain as Lieutenant Raymond Asquith rode on horseback to the crossroads at Fricourt. He’d been ordered by his Brigadier to rendevouz with the prime minister, his father, H.H. Asquith.

As Raymond waited two staff cars eventually pulled up. Father and son were briefly reunited, surrounded by “barking guns” in the distance. Before the assembled could fully gather, a shell whizzed over and landed a little beyond them. Quickly, the group scrambled into a captured dugout, waiting until they got the all clear. Raymond later reported to Katharine, that the “P.M. was not discomposed by this,” in contrast to his General Headquarters chauffeur who ended flat on his belly in the mud. His father drove off after their meeting to lunch and Raymond returned to his billets. Departing under “a bright sun with a touch of autumnal crispness in the air,” this was to be the last time they’d meet.

Soon after Raymond would clamber out of a trench to lead his company under heavy shell and machine gun fire at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. A bullet went through his chest. Immediately aware of the fatal nature of his wound, determined to project a sense of calm to his men, in one last courageous act he lit a cigarette and awaited the stretcher. Of the 22 officers in Raymond’s battalion only 5 survived the battle alive or without serious injury.

Their task had been colossal. The toll they took commensurate with the risks Raymond would have been all too aware of in a war he saw as increasingly futile. They were attempting to take the infamous ‘Quadrilateral’, a heavily fortified German fortress, and the village of Lesboeufs. It took a further three days of fighting for the Quadrilateral to eventually be taken. A week for Lesboeufs. Despite the introduction of tanks to the field of human conflict in this offensive, beneath his unflappable and stoic nature Raymond had seemed quietly aware of and resigned to his chances of survival. Signing off from his final letter to Katharine, dated 12th September 1916, he wrote:

“It would be not altogether disagreeable to come back and do something at the War Office during the winter months. I am getting terribly tired of not being home, and not seeing sweetest Fawnia [his nickname for Katharine]. But I must see out the fighting season. Tomorrow we shall move forward again probably into the line. Angel, I send you all my love. Remember me to Trim [his nickname for his son, Julian, born during the Great War and the last of his three children].”

Raymond died on September 15th 1916. It wasn’t until the 17th that the news reached home. At 9.45p.m. Margot Asquith was called to the telephone at The Wharf, the country home in Oxfordshire where the Asquith’s had been hosting a weekend gathering. The PM was relaying stories of his time with Raymond and gushing over the organisation of the British and French troops. His second secretary was on the line to Margot and relayed the news. He then rang Mells to reach Frances, so she could break the news to her daughter. Back at The Wharf, Asquith met his wife in the corridor. Upon seeing her face he knew what had happened.

It was from the failures of the Somme offensive that Asquith, by then 64, would never recover. Weeping at his desk, he had lost his eldest son. Soon he would lose the political authority of his government. Throwing himself back to his work he increasingly began to display the personal and political toll of the war. The strain was near unbearable. With allied troops faltering in the muds of France, so too did the destiny of the man who had occupied 10 Downing Street for nearly a decade. With British casualties rising, little territorial gain visible, the Somme had become the swamp, sucking young men into its mire. By December 1916 Asquith had been replaced by Lloyd George, who had pushed a split in the liberal party and with support from influential Conservatives and press barons, seized the initiative to form a new coalition government.

Katharine was inconsolable at the loss of her husband. Despite her making him promise to take a job behind the front lines if offered one and the attempted arrangements of his father, he died with his men in the thick muds of France. Raymond had been too honourable. He knew the contempt the General Staff were held in by those suffering on the front lines. A model of classical integrity, it seems that although Raymond was under no illusions about what the trenches would bring or his increasing frustrations at the insanity of the conflict, he couldn’t, wouldn’t, escape his destiny.

Mells and his courtship with Katharine there had meant a great deal to Raymond. It’s therefore fitting that the eleven lines of Latin that form his memorial in the village church are literally cut into the stone. A bronze wreath of olive branches is placed above. Below, two hooks are fixed where his sword once rested (since removed for safekeeping). This is the warrior soldier of the Great War remembered. An attempt to rescue some triumph and gallantry from the wreckage of an awful, bloody war.

The memorial to Raymond Asquith at Mells

Mells Park burned to a ruin. An inferno ripped through the night and defied the pouring rain, one night in October 1917. Frances arrived to look on in devastation as the villagers rushed bravely to scramble and save what they could. Her home as a newlywed, the place she’d sometimes dreamed of returning to, was gone.

News reached Edward whilst he was serving in France. At first he was devastated too. Yet upon hearing it was the Park and not the Manor he attempted to put a positive spin on events. Soon a Country Life reporter arrived to affirm that Mells Manor was the true and ancient seat of the Horners. In the midst of war and loss, a quiet defiance still emanated from the Horners of Mells.

Next month Edward took a bullet to the stomach as he stood clearing the village square of Noyelles. He’d thought the day's job done when a group of German soldiers fell back from the church they’d been sheltering in. A sniper got him as he moved forward to give instructions to his men. The Horner heir died on the evening of 21st November 1917. Edward was buried in a roadside grave just outside Etricourt. He’d left Mells to return to France less than two weeks before, given ten days leave in the aftermath of the fire.

Once more the terrible howls of war reached the gentle lanes of Mells. Frances has done all she could to keep Edward away from the Western Front. He’d already been hit by sniper fire during the Neuve Chapelle offensive of 1915. Before this he was unexpectedly asked to dine with an acquaintance of his mother, Sir John French, Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, at his headquarters in Saint-Omer. French offered him the chance to return home and avoid the trenches. He didn’t take him up on the offer. Great new offensives lay ahead.

Following his injury in 1915 a medical board had declared Edward unfit for active service, a reality he’d raged against. Eventually he managed to wrangle a commission to the relative safety of Egypt, which went some way to alleviating his mothers anxieties. Yet, whilst for Raymond the war had been a call to honour and duty he couldn’t evade, for Edward it was something altogether different. During years in which he found himself mired in gambling debt, his reputation tatters, the war provided not only adventure to an impulsive, even reckless soul but purpose; an opportunity to demonstrate his worth in a conflict that no doubt called to his closest ideals of romantic chivalry. By February 1917 he’d escaped in the direction most were trying to leave. He was back in France, many of his Coterie friends already dead, his last actions a fatalistic lament for the ‘Lost Generation’ of the Great War dead.

Though in life Edward had been a caricature of the bumbling, conceited and irresponsible landed gentry, he was also loyal, charming, and loved by a great many. In death, he stands as the proud unyielding knight of his mothers pre-Raphaelite dreams. His bronze memorial by Sir Alfred Munnings dominates the church interior, where he bravely enters the theatre of war on horseback, head held high, the words of Shelley’s elegy on the death of Keats on Lutyens’ plinth below:

“He hath outsoured the shadows of our night”

Frances was moved to tears when she first saw the sculpture but asked Munnings to change it. Edward and the horse had had their heads bowed. This wasn’t right. Sitting beside the memorials to Laura and Raymond, Mark’s gravestone outside, her gorgeous tapestry nearby, Frances was once more curating the Mells she needed in order to carry on. A beautiful, bittersweet public record was being laid out; words and stone that document the sorrow that gripped a family, a community, and a nation.

For all the theatrics and affective aesthetic flourishes of Edward’s life, to read about it is not to dislike him. The record of his words and character reveal a human vulnerability that dwells in us all, to some extent or another. And in the end he had conviction and courage to risk it all. Standing before that memorial statue at Mells is to somehow be transported back to a country trying to wrestle with trauma and loss on a near unfathomable scale. The shell shocked tremors of mens hands, the terror in their nights, the hurt passed down to sons and daughters that echo through the generations. It’s somehow all there. But so is the heart to carry on and shape, in some way, beauty from our precious, short, vulnerable lives.

Defiance in grief - the grand equestrian memorial to Edward Horner

Overwhelmed by the church we decompressed in the snug cocoon of civility which is the Talbot Inn, where curled up dogs snooze beneath their owners, who sit on stools at the bar and pass their chatter over a pub where candlelight flickers over thick old stone and wood. Fed and watered we were readying to continue our way when we came to the village war memorial. Here a marble column rises to support a sculpture of St George slaying a dragon. Either side the names of the war dead are recorded. The memorial is completed by rubble walls and low benches where wreaths are laid below the familiar homely embrace of a line of yew trees. In the centre a panel of Portland stone bears the inscription:

WE DIED IN

A STRANGE LAND

FACING

THE DARK CLOUD

OF WAR.

AND THIS STONE

IS RAISED TO US

IN THE HOME

OF OUR DELIGHT

This was another commission of Lutyens, who created the nation's most famous war memorial, The Cenotaph on Whitehall. The power and simplicity of language. It didn’t say much at all and yet it said almost everything that needed to be said. Composed by the Poet Laureate Robert Bridges these words stopped me in my tracks. The contrast was all there. These men, many of them mere boys, plucked from their ancient villages into the consuming machinery of continental warfare. Their names were here alongside those of Edward and Raymond. Whilst they might not have their own monuments inside the church, each of them was a poignant reminder of the private griefs of a community haunted by the trauma of loss. How can a nation bear such scars? And of course these boys and men wouldn’t have been offered a way out, no olive branches of staff commissions or ‘important’ messages to take home. They would have faced ceaseless terror in a strange land.

Yet, we can imagine the warm summer day in June 1921 at the unveiling of the war memorial. The villagers gathered around servicemen and clergy. The familiar peal of church bells. A Union Jack flapping in the breeze.

The War Memorial at Mells

As we left Mells the clouds began to shift once more. At first a faint shower, soon a fat downpour. We sheltered under an oak tree and looked down from a field on the manor and church. It was one of those curious English showers, sunbeams through bruised violet clouds. All sorts of jumbled up weather. It comes and it goes. So on we went to reconnect with the East Mendip Way and continue our quest for Glastonbury. There was still a long day ahead.

Informed by ancient custom, standard bearers for civility in an ever changing world, the footpaths of Britain are not infrequently out of sync with 21st century realities. Still, they remain. More than once I’ve stumbled across footpaths passing straight through 4 lanes of highway, asserting my freeborn liberties in the face of 70 mile per hour traffic. “Surely this isn’t right?” I’ve found myself muttering, checking and rechecking the map as I prepare to make a dash for it. Elsewhere I’ve negotiated my way across a working gravel processing plant. This is an element of pilgrimage I’ve come to cherish. I think it’s the absurdity of such moments, backed by the ever present possibility of one day uttering those immortal words, “actually, this is a public right of way.”

Similar moments of disbelief awaited beyond Mells. After clambering through a big prickly hedge threaded by barbed wire we let out a cheer, “never question the ordnance survey!” There it was. An old warped stile in the corner of the field we’d entered into and a near extinct path deluged by Jurassic nettles exactly where our map said there should be one. Seemingly the entrance to the path had been entirely forgotten. “Danger Quarries are not play areas KEEP OUT,” read a faded plastic sign on which a child of the 1970’s, drawn straight from a Ken Loach film, held up his grazed arm. On we went, thwacking our sticks, kettled by heavy fencing, pit on one side, road on the other, up past Whatley Quarry. Heavy freight trains clanged past nearby mounds of oolitic limestone. Yet we were on our way.

All the world continues its business and there you are, aside from the central metabolism of things, edging yourself slowly forward. The rain passed. Fleeces and coats wrapped around waists and stuffed in backpacks. It was hot and sticky in the gloom of the footpath. This section of the East Mendip Way is seldom trodden. Along little streams in dense woodland we crawled through heavy foliage. Every now and then we’d see a bootprint or a crushed patch of undergrowth. There had been others, we were reassured. These were the spaces inbetween. I couldn’t help thinking how many thousands of miles of footpath must lay dormant like this; a great wilderness, spread like a nervous system across our landscapes, ready to be explored.

Late afternoon we reached the village of Chantry. Before long the rain was back. I looked up and saw Agathe trudging along the muddiest, stickiest farm track imaginable. It wasn’t even a track. It was simply earth. Thick chunks of sludge wearying our boots. And it would be hours until we reached our wild camping site for the night. In that time we’d cross over the highest point on the Mendip Way at Cranmore Tower; drop down into Cranmore itself through plantation forests, to the old church of St Bartholomew; push on past the East Mendip Railway ever deeper into the secluded lanes of Somerset. The weather was all the time going through its kaleidoscopic motions. Rainbows burst over hedgerows and showers threatened. Agathe’s boots were killing her and mine were stinking and sodden.

Already feeling responsible for having suggested this route, I felt increasingly bad as we struggled along, wincing, checking how much further we had to go. We’d bitten off more than we could chew on this particular day. This was a pilgrimage lesson. When we did finally make it we just had enough light to set up camp and it turned out we were the only guests; an odd fact that left me feeling like we really might have dropped off the known map of the world. The campsite owner emerged from a little hall which was the only building in a landscape of undulating hills and high hedgerows. In receipt of her simple instruction we struggled onwards to where we thought we were going. Inevitably we got lost. I sprinted back to the buildings and told Agathe to wait for me.

Haunting beautiful polyphonic chanting echoed across the fields as I caught my breath outside. A rainbow dipped and bowed to a cluster of stars. Exhausted, I felt strangely emotional. I realised there must have been some sort of community practice going on. Where this community of singers came from remains a mystery to me, save to say every cottage in that part of Somerset must provide a fine voice. Being awkward and English I didn’t have it in me to interrupt the practice to say we’d got lost, even though I’d left my girlfriend in agony on a hillside in yet another shower. Instead, I did what any self respecting Englishman would do. I lingered with intent. They knew I was there. I waited it out and as I did so, I let out a few quiet tears, those lush almost enjoyable ones that comfort from time to time. The rainbow over the hillside had really settled in and flecks of rain whipped on the breeze. It was beautiful. We’d have the tent up soon. It would be ok.

At night I woke up to go to the toilet. Outside moonlight and clouds drifted across the stars. It was ok. We huddled for comfort and shared out the bags of nuts that were the only food we had on us (great planning by me…), we still managed to laugh about Agathe’s feet and my tears. Why hadn’t we just booked a spa break somewhere?

A lonesome tent on a Somerset night

Next morning the sun was out again and we packed up with our spirits somewhat lifted, though really hungry. Our aim for the day was to get to Wells via Shelton Mallet. To leave the campsite we made our way along one of the most magical lanes you could imagine. The hedgerows towered above us, insects buzzed to and fro, and I experienced a deep swelling happiness. Echoes of Mells came as we rested in a little church on the way to give Agathe’s feet a break. Inside the cool and fresh nave was a memorial plaque recording the lives of Allen John Green (aged 19) and Wilfred Henry Carver (aged 21). Both died in the last week of the Great War. Wilfred on the last day: “at no.29 clearing station in France. Nov 11th 1918…their life for their country no man can do more.” It was a sobering moment. Here I was full of the ecstasy of a fine morning in the deep England from which so many young men had say goodbye to, to never return.

We pushed on but the weather was really coming in now. With no news we hadn’t noticed. “Storm Evert” was bustling its way in from the Atlantic. Perhaps that explained the wild temperament of the weather in the previous days and the fact no-one had been on the campsite the previous evening. With the advice being to avoid staying in tents and caravans we decamped to a local inn when we reached the Cathedral city of Wells. As the storm began to rage across south west England we dashed across Cathedral Green to one of the greatest buildings in the world. At the doors we were met by a member of the clergy in a long elegant purple cassock jumbling a heavy band of keys, “oh I was just locking up,” he said. “But it will take me half an hour or so, so many doors. Come in, come in, shelter from the storm and I’ll come find you to let you out when I’m done.”

So it was that we had the most magical half an hour. Wind and rain lashing against the towering symphony of medieval gothic architecture that protected us, I looked forward to an entirely empty cathedral, just a single candle flickering before the strengthening power of famous “scissor arches” completed some seven centuries ago.

Wells Cathedral - a single candle flickers before the medieval 14th century scissor arches

We made it to the top of Glastonbury Tor the next day, avoiding as much of the theme park Arthurian mysticism of the town as we could. The wind was still blowing hard and we let ourselves fall against it and be blown back again. Though Glastonbury Tor would be the end of our journey and where Abbot Whiting had met his gruesome end; and exploring Wells Cathedral alone had been one of the most memorable experiences of all my times on pilgrimage; it was Mells that stuck with me, drawing me in closer and closer.

Glastonbury Tor - the end of our pilgrimage