Ancient Melodies

The Shijia Hutong Museum @ No. 24 Shijia Hutong

"I (Ling Shuhua) am determined to be a writer in the future...So I dare to ask you to take me as your student. There are so few female writers in China, so the world does not know anything about Chinese women's thoughts and lives. This is very unfair considering their contribution to humanity."

- Recollection of a Few Letters

Ling Shuhua

On one of my first visits to Beijing I was booked to stay at a hotel on Shijia Hutong in the Chayangmen Residential District, a few kilometers east of the Forbidden City. I’ll admit I didn't really know what a hutong was at the time - the hotel was simply near where I needed to be for work, looked comfortable from the photos, and wasn't too expensive. But as I stepped out of my taxi into that dark narrow alleyway, I could feel my explorations of the Beijing hutongs were just about to begin.

First morning in Shijia Hutong and jet lagged, unable to sleep, I found myself up before dawn, walking the length the alleyway before the hotel breakfast opened. In pale light the red lanterns outside swayed in the breeze. A few street sweepers were out besides their carts. A trickle of elderly walkers were trailed by little dogs. Bikes and mopeds were being wheeled out from the tangled courtyard residences of the hutong. Beijing itself was unfolding, coming alive as if some giant mechanical toy set off by the rising sun held over the east end of the narrow alley.

At breakfast, I was to learn from a leaflet at my table that the Shijia Hutong Museum, in part funded by a charity the then Prince Charles headed up, was less than 100m away from where I was sitting - the first such museum in Beijing to attempt the preservation of hutong memories.

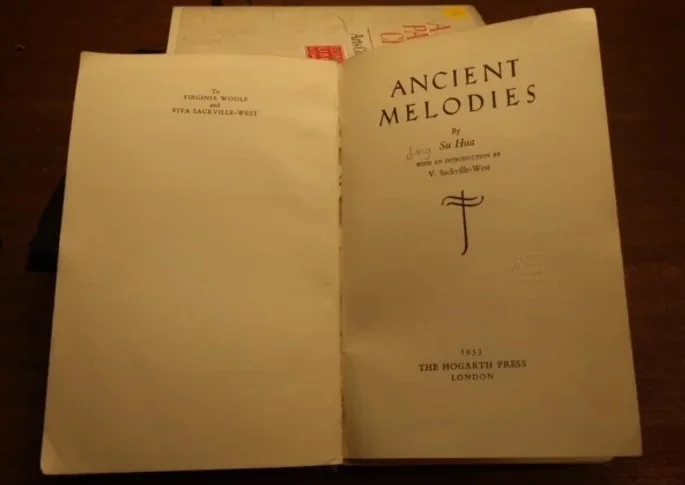

Ancient Melodies

Ling S(h)uhua (1953) Hogarth Press

Shijia Hutong Museum tells the story of a residence, a street, a way of life, and I feel in some respect, reveals something about the sleeping soul of old Beijing.

As you enter the museum, you are taken back to the start of the Hutongs and learn how these strict patterns of urban planning go far back into the history of Chinese cities and can be traced to the Western Zhou period (1046-771 BC). Comparisons are drawn with Manhattan and the grid layout of 19th century New York City. There is great continuity to the Hutongs that remain in Beijing and they give us a glimpse into the warren of a city that once would have been - centered of course on the heavenly astrological and architectural calculations of the Forbidden City. It is believed that Shihia Hutong dates back to the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) and is named after the Shi family ("Shijia" meaning "Shi Family"). The laws of the Ming Dynasty prohibited building illegal houses within the hutongs and were strictly implemented, meaning that even today we can still get a good sense of the architectural layouts from this period.

However, beyond the vast history of the Hutongs, it is the story of Number 24. Shijia Hutong as the home of the Chinese painter and novelist Ling Shuhua that forms one the central exhibition of the museum.

A model of the old Beijing hutongs - the warren now only extant in relative pockets of the city

Ling Shuhua (1900-1990) was the daughter of a provincial governor and sometime Mayor of Beijing during the late Qing Dynasty and describes her life growing up at no 24. Shijia Hutong in her autobiographical novel, 'Ancient Melodies':

"My bedroom had recently been arranged like a real studio. All the furniture had been selected by Father. there windows on two sides. One was facing a large purple wisteria, now in full bloom. The sweet smell was blown into one's nostrils until one almost felt one had eaten the flowers."

Upon marriage to Peking University professor Chen Yuan, the novelist inherited No 24. Shijia Hutong as her home and as stated in the exhibition, 'Ancient Melodies' was written in part to provide a foundation of reality against which to test the pervasive idea of the 'mysterious Orient' in the minds of western readers. Shuhua wrote mostly about daily life, regular experience - description, characters, detail. As I toured the exhibition outlining her works I was slightly bewildered to see the face of Virginia Woolf gazing out at me and a letter from her to Shuhua from the late 1930's, encouraging her literary endeavors:

"...so please consider writing about your life, and if you only write a few pages at a time, I could read them and we could discuss it. I wish we I could do more, and I send you my best sympathy for those of you who are experiencing the war...In fact, I would advise you to come as close to the Chinese both in style and meaning as you can. Give as many natural details of the life, of the house, of the furniture as you like."

How could this be the case? Surely there was an interesting story here? Indeed it was so (though not covered in the museum exhibition). In 1937 Ling Shua conducted an affair with the poet Julian Bell - nephew of writer Virginia Woolf, whom she met while the two were studying at Wuhan University. It was this relationship which opened the door to the long correspondence with Woolf. I've now learned of a novel covering the events of this literary love affair, written in 1999 by Hong Yin - 'K: The Art of Love', an allegedly gross misrepresentation and thinly veiled piece of sensationalism which has been vigorously rejected by Ling Shuhua's family.

One of the little dawn Hutong dogs

Ling Shuhua was to leave China for Britain in 1947 during the civil war. No 24. Shijia Hutong became a factory and, later, a kindergarten (1958-2002), before the creation of the museum. However, the story did not end there. The more I looked into the life of Ling Shuhua, the more fascinating I found the links pointing back to London.

With help from Woolf ’s friend and, of course, former lover, Vita Sackville-West (1892–1962), Ling’s memoirs were edited and published by the Hogarth Press (1953), the printing house of the Bloomsbury Group, with an introduction by Sackville-West.

Arriving home from Beijing and back in England I desperately wanted to get my hands on a copy of 'Ancient Melodies' and cannot quite convey the satisfaction and magic I felt at being handed a near pristine original Hogarth Press copy at the London Library; a copy which appears to have only been checked out a dozen times in the past 40 years.

Indeed, through internet searches I could only find a few articles on Ling Shuhua and her writings and so in the bowels of the London Library stacks I began my own reading of the Ancient Melodies.

As Sackville West observes in her introduction to the book, this "curious correspondence" with Ling Shuhua satisfied the romantic character traits of Woolf, envious as she put it of the "large wild place with a very old civilization." We learn from Sackville West how seriously Woolf took her mentorship role, sending 'The Life of Charlotte Brontë" to China amongst other books:

"It is easy to get books cheaply in London. Please never think of paying for them"

A typical hutong home from the 1950's or 1960's

Sadly we also learn that, "Virginia Woolf and Su Hua never met, for it was not until 1947 that Su Hua arrived in London with a pile of typescript in her luggage." But there can be no doubt about the impact of Ling Shuhua and Virginia Woolf's relationship, even if this was only ever on papers transported halfway across the world.

Reading Ancient Melodies and the subtle, powerful female characters recorded within, I could well imagine Ling reading Woolf's famous feminist treatise, A Room of One's Own (1929), inspired to keep writing, to gain her voice.

As Sackville West writes of Ancient Melodies, "some of the most entertaining passages in these memories are those which relate the complicated daily existence in the sprawling Peking household."

Ling Shuhua - returned to her old home on Shijia Hutong in her final days (1989)

Ling was a female Chinese writer who maintained a clear focus on expressing her perspective as being such. Her letter to Zhou Zuoren at the start of this essay demonstrates this point and Ling was part of legitimating women’s writing in China in the 1920's. It is perhaps ironic, and indicative of the long struggles of female emancipation, that Ling was to remain mute on her mentor Zhou Zuoren in later life. Some have speculated this was because his version of promoting women’s literature centred on a very male-oriented nationalist politics: e.g. women being allowed a voice if it served the right, male dominated, ends.

It's not my purpose here to review Ancient Melodies. However, to highlight how important such writings can be for our understanding of the past there are one or two quiet scenes worth covering. In a chapter titled “Great Uncle,” Ling's uncle, an educated fair minded man who becomes her good friends asks her:

"...what I would like to do when she grew up. I told him I should like to disguise myself as a man to take the Court examination. "My dear child," he said, "I am sure when you are grown up, examinations of all kinds will be open to women."

Through her writing Ling displays the dearth of opportunities for women in China when she was growing up. Elsewhere we hear of a China beginning to change. "Those new fashioned people certainly have missed something as they adopt the Western way," we hear Ling's father say, "They don't respect character writing. You see, character writing is the best way to make one's heart at peace."

I must say I raced through Ancient Melodies, almost like an excited child who opens all their toys at Christmas without truly appreciating what they are being given. I'm now looking forwards to a relaxed reading and taking in all of the delicate drawing's of Beijing which Ling included within the book - illustrations from her own pen.

Of course, much of traditional hutong life has now disappeared. As much as 90% of the original Beijing hutongs have gone, replaced by modern residential tower blocks and wide highways that run through the centre of the city. This said, the Global Heritage Fund estimates that about 600,000 of Beijing’s more than 20 million residents still live in Hutongs today.

Pockets of Hutong life are still present in Beijing. South of Tiananmen Square I got lost amidst the 'Citizens of The Emperor' and 'The long, thin alleys bordered by low, grey houses surrounding noisy, crammed courtyards' as described in Xiaolu Guo's 20 Fragments of a Ravenous Youth (2008). I was pleased to see at the Shijia Hutong Museum that within the Beijing City Master Plan (2004-2020) the concept of protecting Hutong-Siheyuan Architectural styles was included.

At the end of 1989 Ling Shuhua returned to China and to Beijing with the help of her family. She didn't have much time left. Before she died, her daughter and grandson took her on a stretcher back to Shijia Hutong. The children of the kindgergarten (which her former home was now used for) welcomed the novelist with flowers and singing. Taking in the scene the famous novelist was able to whisper, "mom is waiting for me to come home for dinner."

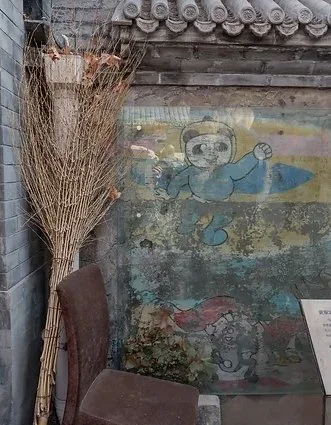

A wall painting from Shijia Kindergarten (1958 - 2002) - memory preserved

In the corner of the museum, a mural from the Kintergarten days is preserved - a fitting memory on which to finish my recollections of Shijia Hutong and the importance of history in the details. For beneath every history, another history.